This is the fourth and final part of my four part guide to Covid masks. In Part 1, I introduced some concepts and explained the limits to my knowledge, in Part 2, I went over some basic information about masks, and in Part 3, I went into some detail about buying masks. In this part, I’ll talk about a few alternative masks, and I’ll go over some basic mask care.

As I said before, I’m doing this with some trepidation because I’m not entirely sure this is the right thing to do. That’s because, to be very clear, I am not an expert in this field. I’ve seriously considered not posting anything at all for fear giving out bad information. But the thing is…I think I know some stuff that might actually help people.

So, now that I’ve fulfilled my duty of explaining my level of knowledge (not a lot, but more than some) and warning you that I might not know what I’m talking about, even though I think I do, let me see if I can offer you some advice about masks.

Note:

If you are a professional, or knowledgeable amateur, who knows more about PPE specifically or medicine in general than I do, and you see that I’ve got something wrong, please let me know.

Mask Use and Care

I occasionally shoot some guns — paper targets and plinking, mostly — so I’ve had firearms safety training, and I’ve learned the basic rules about keeping my finger off the trigger and never pointing the gun in an unsafe direction. Another of the safety rules is “Always treat every gun as if it were loaded.” That means that even if you’ve unloaded the gun, you don’t go waving it around and pointing it at people. You always handle it safely.

I try to take a similar approach to wearing a mask (and other infection control matters, such as hand sanitization). I just always wear one if I’m likely to run into other people. Always is a simple rule to remember.

And yes, I do wear the mask over all my face holes, like you are supposed to.

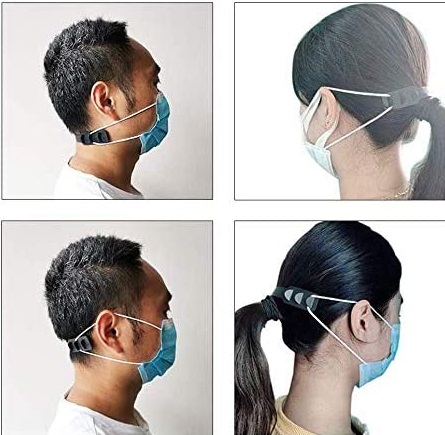

When wearing ear loop masks — procedure or KN-95 — I’ve found it difficult to get a good fit without hooking the ear loops on some kind of mask extender. That allows me to move the mask extender up and down and adjust how far back the ear loops attach, so I can get a snug fit across my face.

Personally, I find cloth masks easy to breath through, and procedure masks aren’t much worse, but when I move up the protection scale to N-95 filtering facepieces, I find that breathing gets harder.

There is some evidence that respirators will cause you to re-breath a little extra little carbon dioxide, but the result is no different from what happens if you exercise, causing your body to produce more carbon dioxide. In either case, the solution to rising carbon dioxide is to take slightly deeper or more frequent breaths to increase the rate of gas exchange in your lungs. You’ll do this automatically, as you do when exercising, but you might find it more comfortable to transition if you force yourself to breath a little heavier, until you get used to the mask.

Another problem I noticed when wearing a respirator is that it functions a bit like a scarf, trapping warmth near my face, which make the air coming in a little warmer. Over the summer, this would get uncomfortable if I exerted myself. I suspect that people with medical conditions such as COPD would need to be careful wearing a respirator.

Mask Reuse

Cloth masks and respirators with replaceable filters are supposed to be reused, but all of the disposable masks I’ve described were intended to be used once and discarded. Given the shortage, however, even frontline medical personnel have to reuse masks for days, and you’ll probably want to do so as well, unless you are using cheap procedure masks, and even then you’ll probably want to keep the mask all day.

The CDC has approved reusing N-95 masks 5 times, but that’s under healthcare conditions. You can probably get away with more, but keep in mind that particle filtering masks do get clogged with particles and eventually you’ll need to switch to a new mask.

But in the meantime, you can use the ones you’ve got over and over…

Donning and Doffing

Since a used mask might be contaminated with Covid-19 virions, you should handle it carefully so as not to contaminate yourself. Here’s a nurse explaining the careful procedures for doing this in a healthcare environment:

There are quite a few of these videos on YouTube, and from watching several of them, the key points seem to be:

- You should assume the outside of the mask is contaminated, and you should be careful not to handle the mask in a way that would transfer the exterior contamination to

- the inside of the mask or

- your face.

- In other words, if you have to touch the outside of the mask, don’t touch the inside of the mask or your face until you’ve sanitized your hands again.

- Whether putting on the mask or taking it off, sanitize your hands twice: Once before handling the mask, and again after you are done handling the mask. (I keep a small refillable bottle with me whenever I’m out for just that purpose.)

- Note that the nurse is using gloves. As she points out, she removes them incorrectly to save them. The correct procedure is a glove-in-glove technique.

Don’t worry if you don’t get it right every time. Unlike these nurses, you’re not working a Covid ward, so you have a lot more leeway to make mistakes. Just try to get it right as often as you can.

Masks can wear out in a variety of ways which you should watch out for. Try to notice if breathing is getting more difficult, and inspect the mask for worn or soiled filters. Don’t forget to inspect the straps, which can wear out or be damaged by use.

Sanitizing Masks

Reusable masks — both cloth masks and reusable respirators — are made of all kinds of different materials, some of which require delicate soap-and-water cleaning, some of which you can toss in the washing machine, and some of which you can put in boiling water in a microwave. Regardless of whether it’s a simple source control mask or an actual respirator, you have to read the manufacturer’s instructions to sanitize it the right way without damaging it.

Disposable masks, on the other hand, were never meant to be reused, so there won’t be any cleaning instructions from the manufacturer. The users of the masks, including healthcare workers, have been trying to figure out the best way to sanitize them. I’d like to tell you what works, but I’ve seen some contradictory information, and I’m not sure what works best. The CDC seems to be very suspicious of the whole idea, and while they have approved some decontamination devices, they don’t endorse a do-it-yourself process.

Nevertheless, people are doing it. The basic approach seems to be some combination of heat and time. During the summer, I used to just leave masks in the car on a sunny day, when the interior got up to about 130°F (yes, I measured it). I don’t know how long it takes to kill the Covid-19 virus, but the FDA pasteurization tables say food is safe after 2 hours at that temperature, so I figure a couple of days should make extra sure.

Now that it’s cooler, I just leave masks sitting somewhere for a week or so and let time and air destroy the virus. (I briefly thought of leaving masks hanging over a heating register where the warm dry air would sterilize them more quickly, but came to my senses and realized this could blow Covid all over the room.)

Recently, I’ve seen explanations of how to use mild heat to sanitize disposable masks in electric cookers. Here’s a video explaining a process developed by scientists at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign:

That sounds plausible, and they’ve got a paper out describing the process, but they make it clear they offer no guarantees, and they have no idea how much you can safely deviate from this process. A different cooker, for example, might overheat and damage the masks, or it might detect the overheating condition and shut down before decontamination is complete.

Also, unlike these scientists, you and I have no way to measure how effective the decontamination process was, and no way to test the filtration efficiency of the masks to make sure they haven’t been damaged. If you try something like this, and I’m not saying you should, keep the temperature under control and inspect the masks for damages.

If you look around, you can find other videos showing other ways to decontaminate masks. The do-it-yourself community hasn’t yet settled on a way that is effective and difficult to screw up.

Meanwhile, I have heard of a few things you probably should not do when cleaning a mask:

- Don’t use a high temperature process because that could melt the mask or the straps.

- Don’t put the mask in the microwave. The metal parts used to shape the mask could be damaged and start a fire.

- Don’t use chemicals like chlorine, alcohol, or hydrogen peroxide. Some of them are dangerous to handle, especially if heated, and they could damage the properties of the filter that allow it to collect small particles. Also, you don’t want to be inhaling some of those fumes when you wear the mask all day.

And now, one final topic…

What’s the Ultimate Respirator?

I was going to put this in the buyer’s guide section, but it was getting too long, and this is not really a serious option, but I wanted to figure out the ultimate price-is-no-object respirator that would give you the most possible protection.

Realistically, it’s probably just a hard-to-get medical grade N95 filtering facepiece respirator, or maybe a half-mask with appropriate cartridges and a filter for the exhalation vent.

But unrealistically, there are a couple of fun options:

In theory, this kind of firefighter-style Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus (SCBA) setup with a tank of air on your back would do the trick nicely, but it’s really impractical and you have to replace the tank every 60 minutes so you need to carry around a lot of spare tanks if you’re going to be out for a while.

If you’d rather carry around batteries than air tanks, you can get a Powered Air Purifying Respirator (PAPR):

PAPR systems use a full hood over your face that is fed filtered air from a battery-powered blower that you can hang around your waist. The blower creates positive pressure in the hood so that all air movement is from inside the hood to outside, preventing any droplets or aerosols from traveling the other way and infecting you.

Even with a loose fitting hood (pictured above) you get at least twice the protection of an N95 mask and you can keep your facial hair. With a tight-fitting hood, PAPR systems are extremely effective — some are rated to provide 100 times the protection of an N95 mask.

Sadly, both the PAPR systems and SCBA come with a number of downsides:

- They are expensive. PAPR systems cost between $1000 and $3000 and SCBA systems cost between $2000 and $4000. (I have no idea what you get for the higher prices.)

- These are complex pieces of machinery that require training and maintenance and refilling of tanks or recharging of batteries.

- Both systems spew waste air out into the environment, making them almost the opposite of source control. If you have Covid, these will make sure everybody around you gets it.

Leave a Reply