In part one, I recounted Tasha’s first full year with us, filled with accidents, surgery, and lots of fights with one of our other cats. Now that all that was behind us, we figured life with Tasha would be a lot less stressful.

But Tasha is not a less stressful kind of cat.

About eight weeks ago, out of the blue, I noticed that Tasha was limping pretty badly. She would put her right rear leg down only briefly and move her left rear leg as fast as possible, as if putting weight on her right leg was painful.

It’s hard to judge injuries with cats. I remember that shortly after we got Beezle as a kitten, he took a bad jump and was limping and mewling piteously, so we took him to the emergency vet. After taking an x-ray, she told us he was fine. As she put it, “Kittens are dramatic.”

On the other hand, Tasha was a bit more than a year old, and adult cats are famous for hiding pain to avoid appearing weak. If she was showing this much pain, she was probably hurting pretty bad. We figured it would be best to drive her to our local emergency vet. After examining her, they said she didn’t seem to be too seriously injured, but they recommended an x-ray to check her bones to be sure. We agreed, and the x-ray showed she had indeed broken a bone in her right leg.

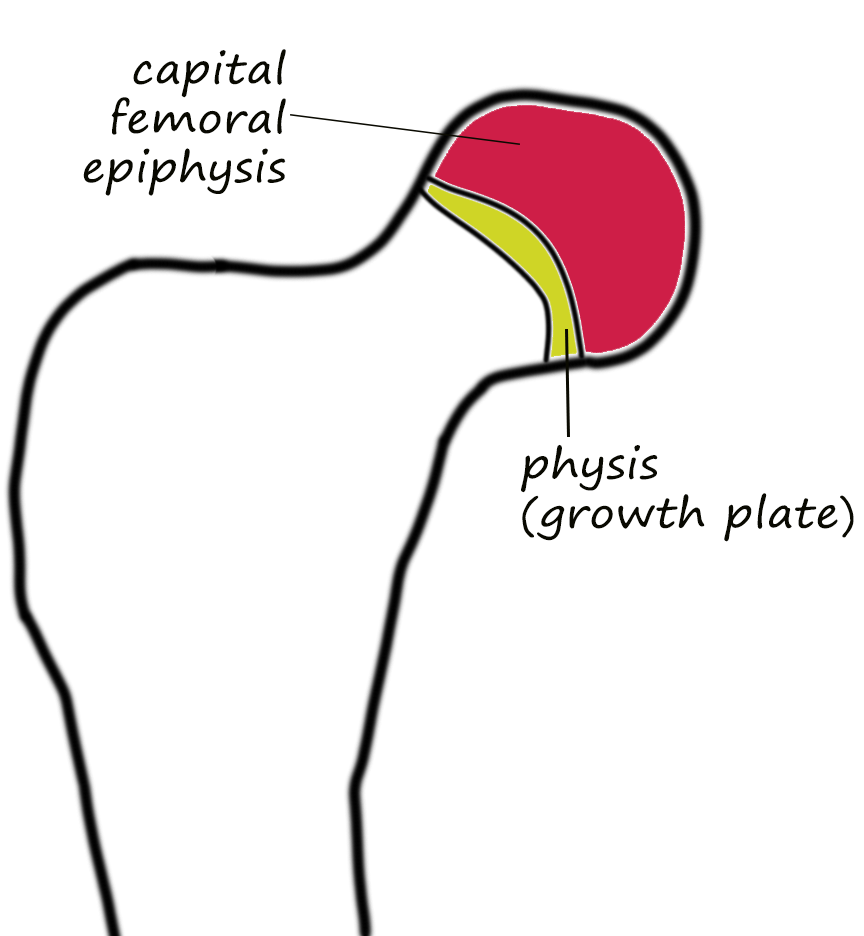

In particular, she had a slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), also known as a capital femoral physeal fracture. I don’t know much about orthopedics, but let me try to explain it as best I can: In a cat, the femur is the single strong bone in the upper part of the rear leg — analogous to the human thigh. It’s big and strong in most mammals. At the top is a bulbous or dome-shaped structure called the epiphysis that sticks out to one side. It’s this bulb that fits into the hip socket and allows a wide range of movement. Between the epiphysis and the rest of the bone is a thin layer called a physis, also known as a growth plate. It looks something like this:

The physis is living tissue, mostly cartilage, that forms new bone across its lower surface, lengthening the bone as the animal grows. When the period of growth is over, the physis closes up to become solid bone. But until that happens, the physis is weaker than the surrounding bone, and as an animal grows larger, the stress on the bone increases with the need to carry more weight. For reasons not entirely understood, in some cats ordinary physical activity can stress the physis enough to cause a spontaneous fracture, separating the epiphysis from the lower part of the bone. This is what happened to Tasha.

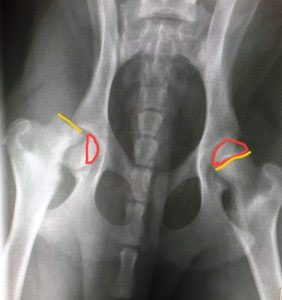

I don’t have Tasha’s x-rays, but here’s a similar one I found online: The view is of a cat’s pelvis seen as if the cat were lying on its back with legs extended and you were looking down at its hips. The hip joint on the left side of the image (i.e. the right hip) shows the epiphysis has broken off and slipped away from the top of the femoral bone.

To make it clearer, here’s the same image with the growth plate highlighted in yellow and the epiphysis highlighted in red on both sides. (I think. I am not an orthopedic veterinarian.)

This generally needs specialized surgical repair, and the vet recommended a surgeon. We left with a small bottle of gabapentin pills to help alleviate pain and discourage Tasha from being too active. A few days later we took her to a specialty veterinary surgeon to see what he could do to help her.

It turns out that veterinary orthopedic surgeons fix femoral physeal fractures using a surprising procedure called femoral head ostectomy (FHO), in which they cut off the top of the femur and discard it, along with the broken-off epiphysis. I found an x-ray showing the result: Note the joint on the left side of the image has had the FHO, which you can compare with the normal intact joint on the right.

After FHO, the bones of the hip and femur are no longer in contact, but the joint still works, held together by scar tissue, ligaments, and the cat’s very strong jumping muscles. We were told the surgery has a very high success rate, and while it wouldn’t restore mobility 100%, Tasha should still be able to do normal cat things like running, jumping, and climbing.

In a human, you might try either replacing the hip joint with artificial components or using screws and pins to reassemble the femoral head. Both of these are possible in cats, but we’d need to have the procedure done in a good university veterinary surgery department, and the cost would be very high.

As it was, the FHO procedure would cost about $4000.

The surgeon had an opening the next Monday morning, so we set up an appointment, got more gabapentin, and kept Tasha dosed up until the morning of the surgery. We got up early, got Tasha in her carrier, and dropped her off at the vet. Later that day we picked her up, quite warn out, and took her home.

Although she had a long-lasting painkiller injection at the site of the surgery, we also had more drugs to give her. We had to confine her to one room by herself for several days so she wouldn’t re-injure herself with too much climbing, jumping, or fighting. As with her previous surgery, she immediately removed the protective collar.

Over the next couple of weeks she got a lot better. We took her to her first surgical follow-up, and the vet told us she was doing so well there was no need for a second follow-up. Pretty soon she was starting to jump onto the couch while I was watching television and climb the furniture in my office when I was working. She kept getting better

…until she didn’t.

I had noticed that her level of activity seemed to be declining. She moved less, she was still limping a bit, and she stopped jumping on the couch. The change was so subtle, I thought I might be imagining it, but one day I happened to see her climbing into the litter box, and she had to struggle at it, gingerly climbing in one leg at a time. This was not how she normally did that. And when she walked away, she was once again moving one rear leg quickly to spare the other.

I called the vet to setup the second follow-up exam. When we got there, he examined her right leg and said it looked fine, so he released her to walk around on the floor for observation. Meanwhile, I started explaining what I had seen that made me bring her in. When I mentioned her moving her leg really quickly, the vet asked me “Which leg was she moving quickly?”

I thought about it, and light began to dawn… The quickly moving leg had been the one on the right, the one that had the surgery. So she was actually protecting her left leg. And while we were talking, she did it again in front of us.

Veterinarians don’t entirely understand why some cats get capital physeal fractures. It’s not a matter of lifestyle because by definition the break happens spontaneously, without any obvious incident like a fall or getting stepped-on. It seems that some cats are simply prone to it. The current theory has to do with reduced blood flow during bone growth causing a weakness around the physis. But whatever the cause, it’s well known that the propensity to this kind of femoral fracture affects both back legs.

Yeah. Our little adventure cat had managed to break the femoral head in her other back leg. She was going to have to go through the whole surgical process again.

It’s now ten days past her second $4000 surgery, and we just got back from the follow-up exam. Again, the surgeon says she’s doing fine and doesn’t need a second follow-up. We were really glad to hear that. We’re also really glad Tasha doesn’t have any more femurs to break.

I feel so bad for her. She’s just a little kittycat. She doesn’t understand why any of this is happening. She just knows it hurts and we keep driving her to scary places and leaving her with scary people and shoving pills down her throat and locking her in the bedroom. She’s had a rough little kitty life.

She looks it, too. Siberian cats are supposed to be big beautiful fluffy cats, and Tasha is exactly that…from the front. But from behind, with her surgical wounds and all the shaved areas, she looks pretty roughed up.

This is a cat that has seen some things. She’s been through the wars.

Leave a Reply