I just saw an article at Reason arguing that the government should stop making COVID-19 tests free. It begins with this dubious statement:

The consensus among scientists and lawmakers after two years of pandemic mayhem is that COVID-19 is officially endemic. That’s good news for those of us looking to move on with our lives, but it also means it’s time for society to make some changes.

Downplaying the Covid pandemic is usually Robby Soave’s beat, but this was by newcomer Elise Amez-Droz, and almost everything in that statement is wrong.

The link in the quote is to a news story about four UCSF doctors who have started a change.org petition asserting some claims about COVID-19 in California, particularly the bay area. I’m not sure if a conclusion can be the result of both “consensus” decision making between equals and “official” top-down decision making at the same time, but an online petition by four doctors at the same university is neither official nor a consensus.

In epidemiology, the word “endemic” sometimes has a specific technical meaning,[1]A disease is endemic in a population if it is present, and if R=1 for a sufficiently long averaging interval, e.g. month-to-month or year-to-year., but more commonly epidemiologists describe a disease as endemic to a population if the disease has a steady caseload or if the caseload varies in a predictable way, such as seasonal variations.

For example, tuberculosis is endemic here in the United States, where it strikes about 9,000 people every year. It varies a bit during the year, infecting more people in the spring and fewer in the fall, and there’s been a decades-long slow decline in cases since the middle of the last century.[2]And the precautions of the COVID-19 pandemic appear to be driving down tuberculosis in recent years. Nevertheless, the size of the tuberculosis problem here in the U.S. remains predictable. It offers few surprises.

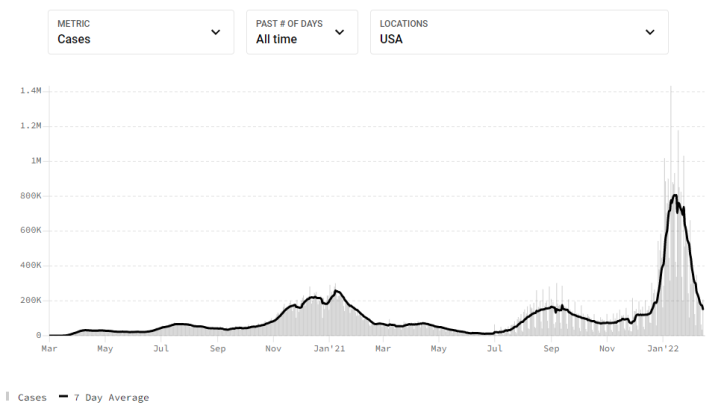

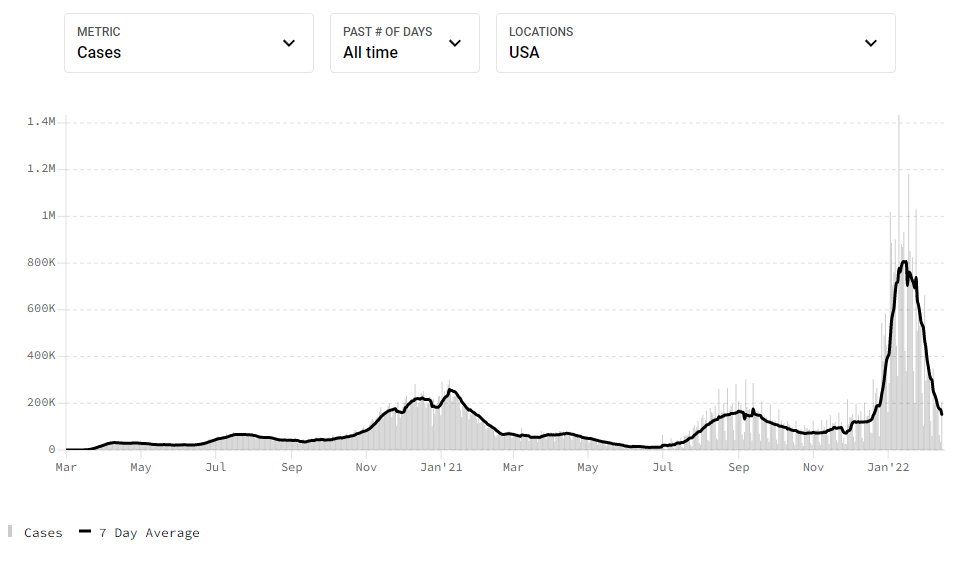

COVID-19, on the other hand, has been anything but predictable. Looking at this chart of historic rates of new cases in the U.S., I don’t see anything I would call “steady”:

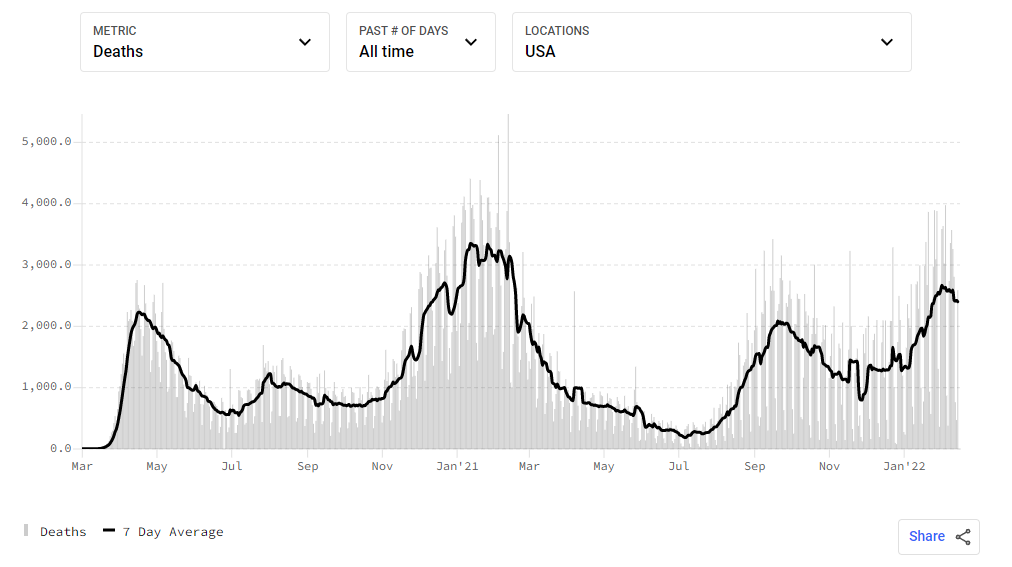

Some argue that the daily caseload is a poor metric for COVID-19 because the reports are subject to variations in testing, especially at the beginning when tests were hard to get, and more recently when people can test at home without reporting the result. For this and other reasons, a straight count of daily deaths is arguably a better measure of the pandemic’s historical behavior. But there’s nothing steady about the COVID-19 death rate either:

Diseases like influenza mix things up a bit. Normally, influenza is endemic, with a seasonal cycle, killing 300,000 to 600,000 people all over the world. But every once in a while influenza mutates into something unusual, and we get a new strain that behaves unpredictably and kills a lot more people — most notably in the form of the Spanish flu, which killed at least 17 million people world wide between 1918 and 1920. In that case, we call it pandemic flu, to distinguish it from normal endemic flu.

As I write this, we only have two years of data on COVID-19. It’s hard to see any seasonal cycles, with the possible exception of a flu-like winter peak in January, and even that is complicated by the fact that the two observed winter peaks were caused by two different variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

During the most recent spike, nearly all COVID-19 cases in the United States were the Omicron variant. But as the Omicron spike collapses, we aren’t sure what will happen next. There was a time when it seemed plausible that we could beat COVID-19, as we had with other respiratory viruses like SARS, MERS, and Bird flu. (That’s certainly what I was hoping for in the beginning.)

Most scientists now believe we aren’t going to be able to eliminate COVID-19 any time soon. Something as infectious as Omicron isn’t going to go away without infecting a lot of people.[3]Unless we find a vaccine that works really well at preventing Omicron transmission. But while it’s fair to say that COVID-19 is going to stick around, that’s not the same as saying it’s already endemic.

To be endemic, Covid would have to settle into a long steady pattern of moderate prevalence rates. It’s true that rates are relatively low right now, and if they stayed that low we’d arguably have endemic Covid. But as you can see from the historic data in the charts above, that has so far never happened. We can’t rule out that it won’t happen in the future — possibly even the immediate future — but it’s premature to say we have endemic Covid right now.

We can’t even rule out a second Delta wave. The Delta variant is still out there. Its numbers are small, because anywhere Delta can go, Omicron can go faster, and there is apparently enough cross-immunity between them that Omicron has forced Delta out of most populations. But once Omicron subsides enough, it’s possible it will leave behind a population that’s still vulnerable to the Delta variant, leading to another surge. All we can do is wait and see what happens.

Heck, we can’t even rule out another Omicron wave. The wave we just went through was the BA.1 subvariant of Omicron, but the BA.2 subvariant has become dominant in the Netherlands and South Africa, and when it gets here, it might cause a new wave of its own. So far, there’s little sign of that, but scientists are being careful not to rule it out just yet. Again, all we can do is wait and see what happens.

And there’s no guarantee this won’t keep happening. We can’t rule out the possibility that the SARS-CoV-2 virus will continue to hit us with strange new variants and brutal waves of infection several times a year. Some of those variants might escape the antibodies created by our current vaccines, requiring us to regularly create and distribute new vaccines, extending what is already the largest vaccine campaign in history.

On the other hand, we can’t rule out the possibility of good news. We might get lucky, and the COVID-19 virus might run into the limits of its natural variability and stop throwing off significant variants. Or perhaps through sheer hard work and perseverance our civilization will beat back the COVID-19 virus to the point where there aren’t enough infected people — and therefore enough active replicating virus particles — to support the a high rate of viral evolution necessary for such frequent variants to occur.

In fact, yes, it’s even possible that we are already there. Maybe we’ve just seen the last big wave of COVID-19 collapse, and the caseload from here on out will just be a steady flow of positive tests, ICU admissions, and deaths. In other words, although there’s no evidence of COVID-19 setting into an endemic state, maybe that’s because it is only just beginning. People have been predicting this for almost two years, and it hasn’t happened yet, but maybe this time is for real.

But even if that’s true, it doesn’t mean we can “move on with our lives” and everything will just return to normal. How could it, when we have a whole new endemic disease to deal with? Like it or not, we will probably have to adapt our behavior to the reality of a new disease affecting our civilization. The world has changed, and we will have to change with it.

I’m not saying it will be all masking and working remotely forever, but some of the features of life over the last two years will likely continue to be necessary if COVID-19 remains a threat. A few possibilities seem plausible:

- Healthcare staff will probably continue to wear respirators.

- Many of the rest of us will probably wear masks when indoors with strangers.

- We may have to keep getting vaccinated for new strains of SARS-CoV-2 if it keeps throwing off new variants.

- Air filtration and fresh-air exchange will likely become more important features of building design and building codes.

- We will probably do a lot more medical surveillance in the near future, so we are less likely to get surprised by new disease threats.

- If we have more COVID-19 flare-ups, we will probably have more masking and lockdowns.

That may sound like a lot of work, but it’s not the first time we’ve adapted to a new disease. Some of us are old enough to remember the days before HIV, when dentists did not routinely wear splash masks and condoms were for preventing pregnancy not death. And our adaptations for food-borne and sewage-caused illnesses are so old that we don’t even think of refrigeration, canned goods, cooking, filtered water, and flush toilets as disease-fighting technology any more, although every one of them is.

Finally, moving on with our lives and returning to normal would mean giving up on the possibility of eliminating COVID-19. Many people claim that “zero Covid” is an impossible dream, and that may be true for now, but we’ve beaten infectious diseases before. Leprosy is easily survivable for most people. Smallpox is just gone, wiped out decades ago by vaccinations and other public health measures. Malaria has been wiped out in much of the developed world, and may be eradicated from a few remaining stronghold regions in another couple of decades.

And then there’s the B/Yamagata strain of the flu, which appears to have vanished from the world. It was last isolated and genetically sequenced from infected individuals in March of 2020 and then never seen again. It’s too early to say for sure, but it’s possible that in implementing world-wide infection control precautions for COVID-19 — masking, social distancing, hand washing, and sanitizing public areas — we may have accidentally driven a major flu variant extinct.

So maybe we could do that to COVID-19 as well. It is no longer a “novel” coronavirus — we understand it better and are better at fighting it. Maybe we can still win if we stay in the fight.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | A disease is endemic in a population if it is present, and if R=1 for a sufficiently long averaging interval, e.g. month-to-month or year-to-year. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | And the precautions of the COVID-19 pandemic appear to be driving down tuberculosis in recent years. |

| ↑3 | Unless we find a vaccine that works really well at preventing Omicron transmission. |

I think that “return to normal” carries a massive semantic load. My opinion is that there’s basically no chance of it ever happening. That there’s the world that we used to have, and the world that we currently live in. That we’re never going to turn back the dial entirely, there will always be people masking out of an abundance of caution, I think our sanitary habits have improved over the last few years, and that sticks around. It’s a question of how much of this new world imprints itself permanently over the old world.

Couple things; from your list:

“We may have to keep getting vaccinated for new strains of SARS-CoV-2 if it keeps throwing off new variants.”

This is wrong. And it’s one of those things where the actual science is competing against a political narrative and the political narrative is winning. The reason that Omicron basically had it’s way with our populations is because the vaccine is not effective against preventing infection for that variant of Covid. The vaccine reduced the likelihood of serious medical complication, but there wasn’t a whole lot of good data saying that the third, fourth, or eighth jab was any more or less effective than the first two. We developed a vaccine for the wild type of Covid, pre-alpha, as new variants emerge, the vaccine will almost certainly drop in efficacy. This should not have confused anyone.

That leaves us with two choices: 1) Develop a new vaccine for the new virus (which I don’t see as nearly as unlikely as I used to.) and 2) continue to do 2022’s version of a rain dance and continue to inject yourself with a vaccine you’ve already taken in the hope that the vaccine mutates into something more effective.

“If we have more COVID-19 flare-ups, we will probably have more masking and lockdowns.”

I don’t think so. I think the appetite for this is long gone. Fact of the matter is that the science hasn’t changed over the last couple of months, but the policies sure have. When we started out on this journey, there was a certain amount of go-along-to-get-along, but after two years of “15 days so flatten the curve” people, generally, are just done. Myself included. There’s a spectrum between the groups I’m about to list, but generally there are two groups of people when it comes to Covid restrictions: The terrified and the annoyed. Up until now, the terrified people were louder, and drove politicians to making more safe, risk adverse policy. I don’t think this is true anymore. I think that most people now know a half dozen people that had Covid, that familiarity took some of the scary mysticism out of Covid, and mitigated, to some extent, what those people were afraid of. Conversely, I have never, in my life, seen so many people marching with signs. Every weekend, there’s a new group out… This last Sunday, I went to Brandon, a city of 50,000 people, and saw a group of 100 people waving signs and flags tied to hockey sticks marching down 18th. The weekend before that, I saw a group of 20 people in Minnedosa (pop 2500) waving all flags. Regardless of what you think of these people (frankly, while I’m there in spirit with them, some of their signs were really effin stupid), I think that they’re, by far, the loudest constituency, at least here in Manitoba, and politicians saw the signs.

I think that we’d need a variant more deadly than Omicron to scare people back into agitating for lockdowns, and because of the reality of the virus lifecycle (variants tend to be more communicable and less deadly) and natural immunities (there are enough antibodies in the population, either natural or vaccinated), that I think it’s very unlikely that will happen.

When I wrote “We may have to keep getting vaccinated for new strains of SARS-CoV-2 if it keeps throwing off new variants,” I meant what you describe in scenario #1 — that the virus might mutate far enough from the original strain that our vaccines become ineffective and we have to develop new vaccines against the new variants, kind of like what we’ve been doing for the flu vaccine for decades.

It’s my understanding that there is evidence the 3rd shot improves the immune system response a lot, and there is some evidence that it does help against Omicron severity. It’s pretty common for vaccines to require a 3-shot series to maximize the immune response, and the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines appear to follow this pattern. They were approved for use before this was known, because nobody wanted to extend the trial periods another six months when it was clear that two doses were pretty effective and we needed to get them out there. So we started the 2-dose regimen and waited to see what we learned from the 3-dose trials. When the results came in, it looked like a third dose would help a lot. (As far as I know, 4th doses are only recommended for immunocompromised people, whose immune systems my not have fully responded to 3 doses.)

As for lockdowns and other interventions, my hope is that we’ll learn enough to figure out what works and when to use it, kind of like we do for weather emergencies. When a snowstorm hits, we advise people to stay off the roads until they are cleared. When a major hurricane approaches the coast, we shut down businesses and evacuate people from its path. When a heatwave hits, we tell people to crank up their air conditioners and stay home.

So maybe we can come up with reasonable, well-defined thresholds and responses for new Covid waves. If they’re clear enough, insurance companies could offer coverage to help reduce the economic costs.