Last year, I wrote my first Jack Marshall day post. I was writing too many posts in response to things that Jack Marshall said in his blog, Ethics Alarms, and wanted to cut back to preserve my sanity. My announced plan was to do just one post a year. Unfortunately that year was 2020, and Jack had a lot to write about. I recently decided that Jack’s posts about the science of COVID-19 pandemic deserve a post all their own, so I wrote this.

I call Jack a “science dunce” in the title of this post as an homage to his practice of labeling people he disagrees with as “ethics dunces.” But Jack’s not a science dunce. He just doesn’t do his homework.

I first noticed this back in 2015, when Jack got ethically alarmed after hearing that Google was planning to filter search results based on “truth.” Jack envisioned Google making all kinds of politically correct social justice decisions about which pages to return in a search. If he had taken the time to find a description of the Google Knowledge Vault, however, he would have learned (as I did) that Google was just researching the idea of tweaking their algorithm to check pages against a set of basic facts — state capitals, dates and places of birth of famous people, book publication dates — drawn from public knowledge databases such as Wikidata. Pages that got lots of basic facts right would score higher in searches. (I have no idea if they ever did this.)

As you might imagine, Jack’s unwillingness to do the homework did not serve him well when writing about the COVID-19 pandemic. In early April, Jack took White House pandemic response coordinator Dr. Deborah Birx to task for saying

The next two weeks are extraordinarily important. This is the moment to not be going to the grocery store, not going to the pharmacy, but doing everything you can to keep your family and your friends safe and that means everybody doing the six-feet distancing, washing their hands.

Jack responded:

It doesn’t figure that the weeks where a sharp increase in deaths are expected would be weeks requiring universal home quarantine, which is what she appeared to be advocating. The virus isn’t going to get more infectious.

[…]

So because there are going to be “lots of deaths” nationwide, that means my precautions suddenly are no good, so I have to resort to living on Halloween candy and old dog biscuits? This makes no sense.

At that time, hospital admissions were skyrocketing, putting some hospitals in crisis care mode, doctors had resorted to sharing treatment tips on Twitter, and the pandemic showed no signs of stopping. It looked like some overburdened hospitals would soon have to make hard decisions about which patients would receive treatment, and which would not.

So the problem was not that the virus would get more infectious, or that precautions didn’t mitigate the spread of the virus. The problem was that if you did happen to catch COVID-19 at that point in the crisis, the hospitals might not have the capacity to help you. Dr. Birx’s remarks didn’t spell this out very clearly, but anyone who had followed the news coming out of the front line hospitals would have understood this point.

By late June, Jack was accusing the media of trying to frighten the public, and he tried to science it up a bit:

Meanwhile, the death rate is declining even as the number of cases spike, and there’s a reason for that. In all outbreaks, a disease claims the most vulnerable first. This is known as Farr’s Law, named after William Farr, a British epidemiologist and early statistician who recognized the importance of death statistics and identifying causation. Not only has the current epidemic claimed many of the most vulnerable in the U.S., thanks in great part to the catastrophic decision of states like New York to send infected seniors to nursing homes, millions of Americans have antibodies.

The combination means that even if there are lots of new cases going forward, the death toll is likely to be far less severe than it has been. Do not hold your breath waiting for the media to explain this.

Just for fun, check and see how many news organizations have mentioned Farr’s Law.

First of all, “Farr’s Law” usually refers to the fact that epidemic death rates often follow a bell curve. Farr also observed that epidemics kill the vulnerable first, but that’s not usually considered Farr’s Law.

Second, the reason the media doesn’t mention Farr’s Law is because it’s not a big part of epidemiology these days. Dr. William Farr was an important historic figure in the use of statistics in epidemiology and medicine, but as was explained in the article Jack linked to, Farr missed one of the fundamental truths about diseases: He didn’t know they were contagious. Faced with Covid-19, Farr would have been searching for miasmas.

Third, the death rate is a lagging indicator. It runs behind the new case rate for the simple reason that most people who die of COVID-19 don’t do so on the same day they are first diagnosed.

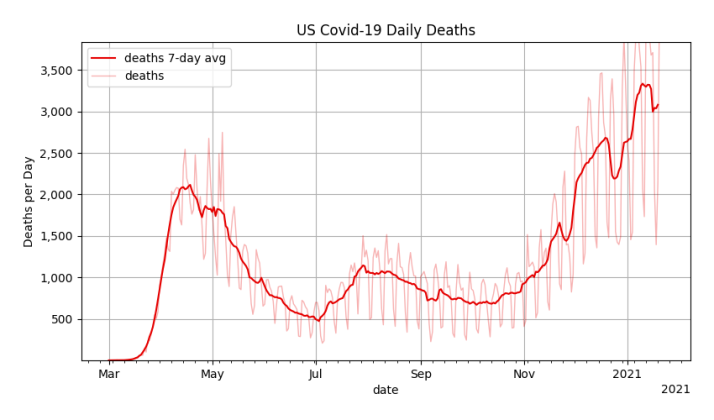

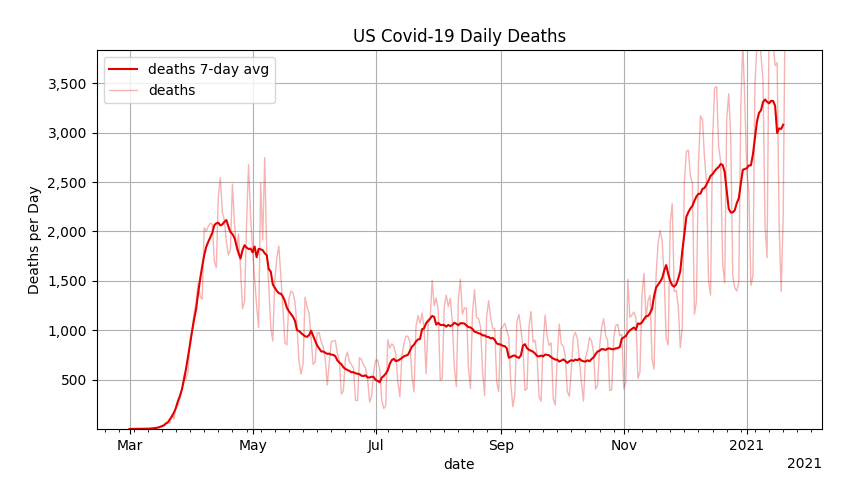

Jack could have looked all of this up before posting. Instead, he wrote that post in late June, which happened to be a low point in the U.S. death rate. There have been two more spikes since then, the death rate eventually rose to more than six times what it was when that post was written, and another 300,000 people have died. Despite what Jack thought, COVID-19 was nowhere close to running out of vulnerable people to kill.

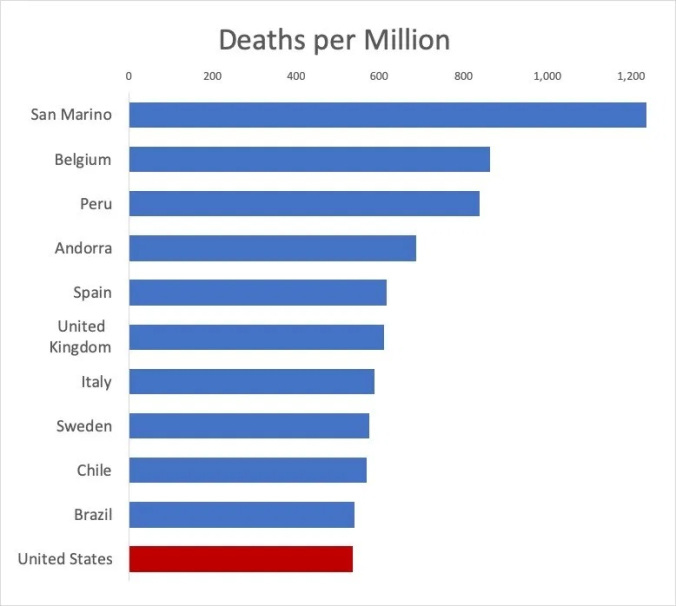

While we’re looking at charts, in late August, Jack argued against the proposition that the US is worst at handling Covid-19. He’s right, of course. The U.S. isn’t the absolute worst. But somehow Jack thought it was worth using this chart to make his argument:

This chart is BS. What happened to the other 180-or-so countries? Based on typical Covid stats, they all had fewer deaths, but were left off the chart. A better comparison would be to pull deaths/million statistics from Worldometers, where the U.S. currently has the 11th highest death rate out of 190+ countries.

In a November post, Jack thought he found a “smoking gun” in an article about Prof. Genevieve Briand ‘s research in the Johns Hopkins News-Letter. According to Jack, the article claims that the total number of deaths in all age groups has not changed because of the virus, implying that deaths due to normal causes may have been recategorized as Covid deaths.

Jack makes much of the fact that the article has been retracted by Johns Hopkins:

Who is Genevieve Briand? She is a Johns Hopkins professor and the an assistant program director of the Applied Economics masters degree program, meaning that she knows how to read and compare numbers. She has no apparent agenda, other than to reveal the truth and allow others to use facts to better understand the world and to make better decisions. Why, then, were the results of her analysis suddenly scrubbed from the web? Were they wrong?

No, they weren’t, at least not on their face.

Yes. Yes they were.

The rest of the editors’ note is attempted tap-dancing and spin to avoid and cloud the natural and reasonable conclusions to be taken from the original article and Briand’s work.

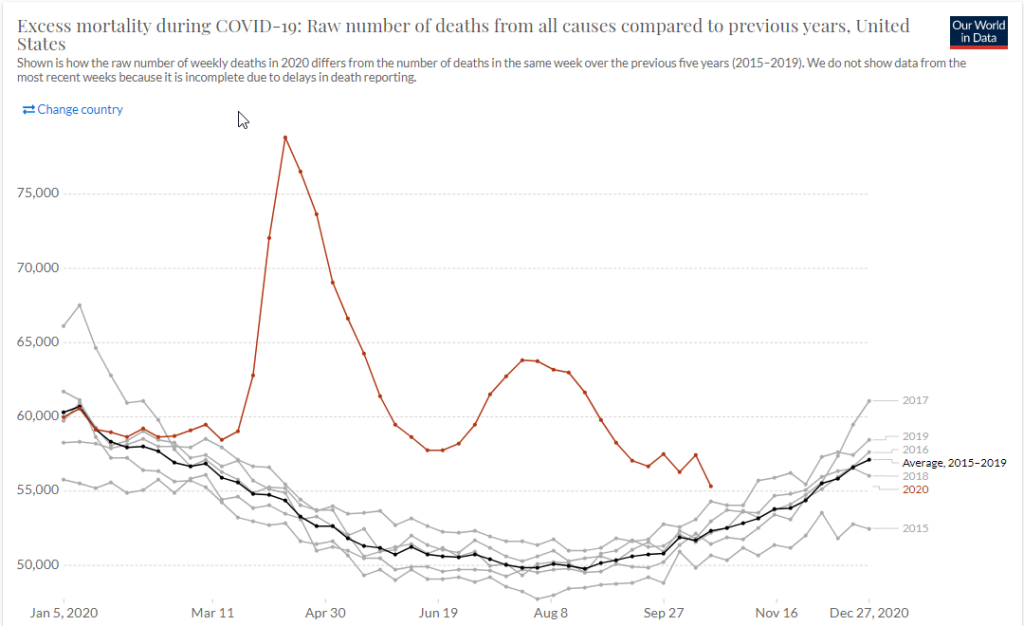

What Jack calls “tap-dancing and spin” is actually the explanation of why Briand’s analysis was wrong. It includes a link to this chart of weekly deaths in the U.S., displayed year-over-year. See that year in red that’s way above all the other years? That’s 2020.

(There have been more deaths since Jack wrote that post. The latest chart is here.)

There’s also this stats page at the CDC. And I found a report from late October, published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (the definitive forum for reporting on diseases and deaths in the United States) which found an estimated 300,000 excess deaths at a time when the official Covid-19 death toll was 198,000. That suggests the official figures were actually undercounting the death toll from Covid-19 by about a third.

Jack complains that Briand’s data is being censored, even though all Johns Hopkins did was add an intercept page with an explanation and a link to the original article. It’s literally just one more click away. But Jack doesn’t do his homework.

The post that finally made me want to write this piece was a rant about masks in early December. Jack was responding to a New York Times article summarizing what scientists have learned about masking.

Thus when the Times published this article, with the sub-head, “The accumulating research may be imperfect, and it’s still evolving, but the takeaway is simple. Right now, masks are necessary to slow the pandemic,” I assumed that I would read an unequivocal, full-throated, air-tight brief for mask-wearing.

Well, it wasn’t. In fact, there is so much equivocation and doubt in the article, which announces itself as pro-mask, that it reinforces the conclusion that the case for masks is being overstated, which is to say dishonestly reported.

Actually, the article provides a succinct summary of the evidence in a single paragraph:

Apart from epidemiological studies showing that mask use is high in countries that have successfully controlled the virus, mask mandates have been shown to significantly slow the virus in U.S. states and in health care settings, Dr. Volckens said.

Jack goes on to respond to several quotes from the New York Times piece:

New York Times:

“Increasing the proportion of people who wear masks by 15 percent could prevent the need for lockdowns and cut economic losses that may reach $1 trillion, about 5 percent of gross domestic product, the C.D.C. said.”

Jack:

Could? Could? So this is just a guess, then, right? A guess by the same organization that regards being wrong and having to retract what it said was true earlier proof of what’s wonderful about “science.”

First of all, to pick a nit, the organization that did this study isn’t the CDC, as Jack implies. Those numbers are from a study by Goldman Sachs Research. The CDC was just referencing it.

Second, of course it’s a guess, because it’s about the future. How could it be anything else? Science is usually a pretty good way to make guesses about the future, because it uses theories that are based on evidence from the past.

(I’ll get back to Jack’s snark about being wrong later.)

Jack then goes through a series of quotes where he complains about the imprecision of the writing in the New York Times piece:

NYT:

The average person, on the other hand, is exposed to much less virus and less often, and so can be protected with a well-made cloth covering, Dr. Brooks said. The best cloth face coverings, which have multiple layers that can trap viral particles — the thickest are mostly impervious to light — are as effective as surgical masks in some circumstances.

Jack:

In what circumstances? What are the standards for a “well-made” mask? I see many people wearing paper masks, and wrote earlier about lattice masks on sale over the web. Are there standards for what masks are effective?

NYT:

“The average person can be protected, at least somewhat, with a well-made cloth covering, according to the C.D.C.“

Jack:

That’s a double indefinite! “At least somewhat” and a “well-made cloth mask” when we have no standards regarding what “well-made” means, because…

NYT:

“All kinds of masks offer the wearer some degree of protection, multiple studies have shown. Exactly how much protection is not yet clear.“

Jack:

Oh.

This is frustrating to read, because Jack is criticizing the New York Times article for not being something it was never intended to be. The authors are using imprecise terms like “circumstances” or “at least somewhat” or “some degree” because they are writing for a general audience and trying to characterize the findings of a complex and still-developing scientific effort that has a considerable amount of uncertainty.

But the imprecise language in the article is a feature only of the article, not the underlying science. Jack is criticizing the science behind public health masking based on a newspaper article. If he wanted to criticize the science, he should have looked at the actual science.

To give you an idea of what the science looks like, I wrote a post last month which briefly summarizes 27 masking studies relied on by the CDC. My descriptions offer a little more precision than the New York Times, but they are still just summaries. The actual science is in the studies themselves, which I link to in that post.

Totaling about 350 pages, that’s a lot to read, but even if you just skimmed them for important information (as I did) you’d learn that scientists have studied a variety of mask materials, and while the effectiveness of the materials varies widely, almost every material offers some degree of filtration that would mitigate the spread of COVID-19 germs. It’s hard to predict how well a specific mask will work without measuring it in a lab, but they all seem to work at least a little.

NYT:

“This discovery became especially important once scientists learned that people who don’t even feel symptoms may spread the virus.”

Jack:

Wait: is it increasing evidence, or is it a discovery? They are not the same thing. This is dishonest advocacy. designed for casual and gullible readers.

Jack’s sort of right, “increasing evidence” and “discovery” are not the same thing, but they are related, because gathering evidence is part of the process of discovery, which proceeds by coming up with ideas and testing them to see if they hold up.

In many cases, however, scientists want to check a general proposition, such as “Does wearing masks reduce the spread of COVID-19?” That’s a lot harder, because a statement like that asserts a universal truth that applies to an essentially infinite number of cases. Since it’s impossible to completely test a universal statement like that — which scientists call a hypothesis — and prove it works in all cases, scientists can never be perfectly certain.

So what scientists do is test a representative sample of cases and see if the results agree with the hypothesis. If they do, then the test is said to confirm the hypothesis. That doesn’t mean the hypothesis is true, but it’s a case where the hypothesis could have been proven false, but wasn’t, thus increasing our confidence in the hypothesis.

Basically, the more we test our hypothesis, the more we can be confident that it is less likely to be wrong. So if we form a hypothesis and test it enough, we can eventually reach whatever level of confidence we need to reach. Science progresses by increasing our confidence in various hypotheses through thorough testing. We sometimes call this process of creating and confirming hypotheses “discovery.”

When I first read this next string of comments from Jack, they made no sense:

NYT:

Critics of mask-wearing measures have long demanded a randomized clinical trial that establishes their effectiveness. But while such trials are the standard for drugs and vaccines, they are not ideal for evaluating behaviors subject to people’s recall, experts said.

Jack:

Boy, those ignorant critics demanding actual proof before they agree to alter the way they live their lives!

NYT:

“Show me the clinical trials that showed the efficacy of hand washing,” Dr. Volckens said. “And I think we all agree that smoking causes cancer and is bad for you — does that mean that we can’t believe that smoking causes cancer because there isn’t a clinical trial?”

Jack:

Do you really want us to list all of the things the public agreed on that turned out to be untrue once actual research and data were available? So we should just believe this because the “experts” say so, I guess. This is the “scientific” argument.

It took me a couple of read-throughs to understand what’s going on: Jack apparently believes that randomized clinical trials are the only way to test a hypothesis.

It’s true that randomized trials are the gold standard of scientific proof, but they are difficult and time consuming, and they involve more difficult ethical issues. A randomized trial for a medical intervention like wearing a mask would require choosing a bunch of people as subjects and then randomly assigning them to either the treatment group, which wears the mask, or the control group, which does not, and then waiting to see if there are differences in the rate at which they catch COVID-19. If fewer people catch the disease in the treatment (masked) group than the the control (unmasked) group, that tends to confirm the hypothesis that masks protect people. Aside from the effort involved, there’s also the ethical issue of instructing study subjects not to wear a mask in the middle of a dangerous respiratory pandemic.

Fortunately, scientists have the alternative of doing observational studies, in which they look at what’s happening naturally in the real world and try to find patterns that support or refute their hypothesis. For some sciences, these are the only possible studies. Astronomers, for example, cannot conduct experiments with stars and galaxies. Nor can any scientist who studies things that happened in the past, such as geologists or evolutionary biologists (or astronomers, now that I think about it). Observational studies are also useful when, as with masking, there are ethical concerns about a randomized trial.

Among the studies on my CDC list are several observational studies that compare rates of COVID-19 spread between geographic regions where people began community masking at different times. The results of these studies are consistent with masking slowing the spread of the virus. There are also a few studies that compared the rates at which mask wearers and non-wearers come down with COVID-19. These studies were harder to do because researchers had to interview individual people instead of just looking at public health statistics, but they found wearing a mask did have a personal protective effect.

This misunderstanding on Jack’s part is why he is confused when Dr. Volckens’s says, “I think we all agree that smoking causes cancer and is bad for you — does that mean that we can’t believe that smoking causes cancer because there isn’t a clinical trial?” All the real-world studies about the dangers of cigarette smoking are observational studies, because it would unethical to tell thousands of participants to smoke cigarettes and it would be impractical to wait decades for them to develop COPD or lung cancer.

NYT:

“A Danish study published on Wednesday was a randomized clinical trial assessing whether a mask protected wearers. It found no statistically significant effect. But the study has serious limitations, experts said: It was conducted when community transmission in Denmark was low, and masks were far from the norm.”

Jack:

The actual study on masks isn’t good enough, but the near-unanimous belief of health experts without studies is to be trusted and obeyed.

This is what I’m talking about. Jack read that there were no randomized clinical trials, but his reaction is that health experts believe things “without studies.” I’m pretty sure he doesn’t know that the “near-unanimous belief of health experts” is backed up by observational studies.

As for the Danish study, it was testing the proposition that wearing a mask protects the wearer. It makes no claims about wearing masks for source control — to protect others when the mask wearer is sick, which is the primary reason health authorities want us to wear masks — so it doesn’t refute the idea that we should wear masks to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

All 6000 participants in the study received basic instructions in social distancing, but half the participants were given masks and instructions on how to use them. No one was told not to wear a mask, but the study authors chose a region where few people were currently wearing masks, so they knew that the control group was less likely to mask up. The study only lasted 30 days, and COVID-19 infections were rare in the area, so only 93 people tested positive, 2.1% of the control group and 1.8% of the masked group. This difference was not considered statistically significant. The best that could be said with significance (i.e. 95% confidence) is that the effect of wearing a mask ranged from a 46% decrease to a 23% increase in infections.

That result is somewhat contradicted by a couple of observational studies: A study of the COVID-19 outbreak on the USS Theodore Roosevelt found that masking was associated with a 70% reduction in risk of infection, as did a case-control study in Thailand. Furthermore, laboratory tests on a variety of masks shows that if well-made and correctly fit, masks can effectively filter the kinds of droplets and particles that can carry COVID-19 virions, and therefore can be expected to reduce the viral dose of mask wearers. In addition, filtering facepiece respirators such as N95 masks are standard issue protective gear for airborne viruses, and randomized controlled trials (2009, 2019) suggest that simple medical procedure masks are as effective as N95 masks against the flu virus.

The Danish study is interesting, but given its limitations, it’s not powerful enough to support any conclusions about the protective effect of community masking. Nearly all of this information was available online at the time Jack wrote his post.

“’It’s hard to do these studies in real life,’” [one doctor] said.”

Jack:

Oh…we should all wear masks without sufficient evidence because actually finding out whether they work is “hard” ! Isn’t science wonderful?

Again, the doctor was clearly talking about randomized clinical trials, which are difficult to do for COVID-19. But there was a paper published back in 2009 that studied the use of masks by parents caring for children with colds or the flu. Influenza is less dangerous than COVID-19, and few parents wear masks when caring for sick children, so scientists avoided ethical barriers by giving masks to some parents and letting the control group do whatever they wanted. The parents wearing masks proved to be less likely to catch a cold or flu.

To summarize, we’ve got a bunch of lab experiments with masks and mask fabrics, a bunch of observational experiments done on COVID-19 in the wild, and a randomized trial on influenza, all of which support the idea that masks slow the spread of COVID-19 and offer some protection to the people wearing them. That may not be as strong a case as we have for, say, the theory of gravity, but contrary to Jack’s mistaken beliefs, public health experts are not just making stuff up.

I think the New York Times set out to make the case for mandatory masks and found that the case was weak, so they engaged in appeals to authority, deceit, cherry-picking and dishonesty. I think that rather than critically examine the justification for the sweeping endorsements of wearing masks, it just resorted to pushing a narrative at the expense of public understanding, counting on their readers to accept what is basically a lot of evocations as fact. I think that if this is the best the nation’s paper of record can do to make the claim that masks are crucial when it undertakes the job—this was a special feature in the Science section!—then the public is being misled, once again, “for their own good.”

As impressive as the New York Times “Science” section may be, they were presenting a summary of the science, not doing the actual science.

What the Times article essentially says is,

“Health professionals don’t really know how much masks will prevent the spread of the Wuhan virus, but it’s probably better than nothing, and since they don’t care at all about the many, many negative consequences of doing it, we’re expected to do what they say.”

This is nonsense. I just included it because I’m wondering what the heck he thinks the “many, many negative consequences” of wearing masks are. He doesn’t say.

Finally, I want to address one more misconception Jack has about science. Back in May, he was discussing the decision making process for re-opening the economy, and in the midst of some good points, he made a very dumb point:

No one can rely on “experts.” First, they don’t agree, so the opinions of experts in various fields can be cherry-picked to support a wide range of options. Second, their record in this episode stinks.

Let me start by pointing out that experts very quickly got many things right: That the illness spreading in Wuhan was a new disease, that it was a virus, that it was of the coronavirus subfamily, and that it had the potential to cause a pandemic. They quickly sequenced its genes and begin devising vaccines. Medical doctors began to protect themselves and patients with gowns and masks and gloves and alcohol and controlled airflow. They knew how to diagnose lung damage and they treated serious cases with high flow oxygen, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, and intubation. When the disease caused complications, doctors were ready with treatments for many of those as well.

Experts improved on some of this stuff as they learned more about COVID-19 — as they learned about asymptomatic infection, aerosolized spread, new uses for old drugs, and how best to use ventilators — but they got a lot of stuff right very quickly. We don’t talk about it because it’s not news, but it still ought to count. Or to put it another way, of course experts have a terrible record if we only look at their failures.

Also, just because the experts made a bunch of mistakes doesn’t mean we should make up whatever random nonsense we find more satisfying. And unlike many people with random guesses, the experts have been correcting the things they got wrong, because that’s how science works.

Jack doesn’t like that argument.

One section of the article is headed, “Over time, recommendations on masks have changed. That’s how science works.” Wait, aren’t we always being told that challenging conventional scientific “consensus” is being a science denier?

Not when you do it with evidence. Good evidence. Then challenging conventional science is just more science.

Skepticism is just a caution that what is being pronounced as the absolute answer isn’t as certain as its advocates claim. Here, the Times is saying that science being proved wrong is “how science works.” This obviously a procrustean standard at best. “Believe what we say, because we are scientists, but when it turns out we were wrong, that just proves how trustworthy we are.”

Well…yeah.

Revising your beliefs about the world when faced with evidence that refutes those beliefs is what you’re supposed to do.

What’s the alternative? Zealously clinging to your beliefs about the world in the face of all evidence that they’re wrong? Denouncing the evidence rather than trying to understand it? Dismissing the evidence as “fake news”? Divine inspiration? Just believing what sounds right without ever examining why?

There’s nothing wrong with being skeptical about some piece of science. But if you want your alternative theory to be taken seriously, you have to learn about the science you’re concerned with, address the evidence for the other theory and, show evidence that your theory is better.

Much of the time, science is the tedious process of thinking of new ideas and then discarding them when they don’t survive a test against empirical evidence. Those ideas that remain — those that pass test after test against the real world — become new scientific knowledge. This is the basic naturalist philosophy of knowledge — by way of Popper, Hempel, Kuhn, and Quine — that guides all modern science.

When operating on the frontiers of science, the process of gaining knowledge can be frustrating and fickle, changing direction with every new new bit of data, leaving us with little confidence in what we know. But we have found no better alternatives. There are no shortcuts to scientific knowledge. This sometimes frustrating process is still our best hope.

I generally agree with you, but I think that we as people have given “science” too much importance in our day to day lives.

Don’t get me wrong, science is important, and I’ll never say otherwise.

But science is also slow. And we haven’t studied everything. Science is by it’s nature incomplete. And it seems like one side of this discussion routinely likes to ignore reality until they have a study or an expert to back them up, and it’s leading to a couple of problems: First off, they’re acting absurd, and second, they’re hemorrhaging credibility at a time when credibility is needed.

As an example; It was very obvious, very quickly, that the virus was airborne, and masks would help. I remember pointing out in April or May that countries that had mask mandates had a much lower infection curve, on average, than countries that didn’t. At that time, American Democrats were saying that people buying and wearing masks were tin foil hat conspiracy theorists depriving hospital staffs of PPE.

As another example; You’ve talked about the study that was used to justify the first round of lockdowns, the study where a couple variables meant the difference between 2.5 million Americans dead in year 1 or 250,000.

Time and time again throughout this process, “science” has been wrong. And that’s OK, science doesn’t need to be right every time, science helps us understand the world around us, but it’s uniquely bad as a tool to drive policy. Lazy legislators and political hacks are using “science” as an infallible cudgel, while only really listening to the science that reinforced their prior positions.

Anthony Fauci is being lauded as some kind of great mind when it comes to the pandemic, but he has taken basically every position on every issue, admitted that he’s lied because he “thought the public wasn’t ready for the truth” (this was in reference to the point the population would have herd immunity), and spoken gravely about the importance of masks while being pictured not wearing a mask in close proximity to other people. If he’s the guy, if he’s the expert, if he’s the science soothsayer, what the hell are we supposed to do with that?

That’s not even starting to take into account all the hypocrites who gravely speak of the importance of adhering to the rules, minutes before breaking them about a dozen times over by getting on planes to join their family who took different planes to get to their parents place a state over. Or the idiots who put out ideas like isolating family members in different rooms of the home, or masking during sex. Help fight the pandemic! Do it doggy! Speaking of Dogs, you might be able to catch Covid from your pets, or not, depending on who you listened to and when. But just to be safe, maybe get them put down at the vet (yup, that happened).

I can’t blame people for not being in lock step with these guys, when lock step adherence to the rules is often facially absurd, changes depending on who you’re listening to, and can reverse 180 degrees on a dime. I give Jack a great amount of leeway when he’s criticizing people for not being precise, because those imprecise theories are being used to mold public policy. If we’re going to use “SCIENCE!”(TM) as the basis for all public policy, then “SCIENCE!”(TM) better be pretty fucking infallible.

I’ve been meaning to reply, but I’ve been busy. Finally got around to it here.

“She has no apparent agenda,”

I learned a long time ago that when Jack says this, what he means is “They have the same agenda I do, but I will pretend that they are neutral and objective, just as I pretend that I am.”