Now that we’ve had a second recent election in which the candidate who won the popular vote ended up losing the electoral vote, lots of people are talking about getting rid of the Electoral College. My gut feeling is that it would be a good idea, because it seems like an unnecessary complication that violates the one person, one vote principle, but I’m willing to be persuaded. There’s one argument, however, that just doesn’t work.

FACT: @HillaryClinton won the popular vote because of California, NOT the Nation. Let that sink in. America Spoke!! https://t.co/0tAwxPSEPF pic.twitter.com/swqZOWXiMw

— BraveHeart (@Braveheart_USA) December 19, 2016

That’s a little…simplistic. Maybe let’s look at the Federalist Papers Project post by Robert Gehl that he links to…

If the election was decided by the popular vote, than we would be swearing in a President Hillary Clinton.

But that’s not how it works. And – as he has said many time – if Donald Trump was campaigning for the popular vote, rather than the electoral vote, he would have campaigned much differently.

Perhaps he would have spent more time in California – a state that voted overwhelmingly for Hillary Clinton.

But he didn’t and Hillary’s margin of victory in that state was 4.3 million votes – or 61.5 percent

And therein lies the rub.

The purpose of the Electoral College is to prevent regional candidates from dominating national elections.

California is now a one-party state. There were zero Republicans running for statewide office and no GOP candidates in nine of California’s congressional districts. At the state level, Investor’s Business Daily reports, six districts had no Republicans for the state senate and 16 districts had no Republicans for the state assembly.

Clinton was going to win California’s 55 electoral votes, so Trump didn’t campaign there.

That argument is a real muddle. For one thing (and you can’t imagine how much it pains me to say this), Donald Trump is right: If the election had been based on the popular vote, he would have changed his campaign strategy. So would Hillary, of course. As a result, you can’t project the results of a popular election system using the popular vote obtained under an electoral voting system. The systems just work differently. Both candidates knew that the results of the election would depend on the electoral college and they shaped their campaigns for that system. Voters knew it too — pundits have been talking about it for a year, and swing state voters couldn’t go ten minutes without someone telling them how important their vote was — and all that would have figured into their choices, including the choice of whether or not to vote.

(This is also the error made by people who say that Hillary’s popular victory gives her a moral right to be President: By definition, she only won the popular election among voters who made their choices knowing that the popular election didn’t matter. It’s not clear she would have won under a straight popular vote after both candidates spent half a year campaigning for that vote.)

This is why Gehl’s argument is incoherent: On the one hand, he argues that a popular election would be unfair because it gives Californians too much power, and on the other hand he argues that Trump could have won a popular election. I don’t think you can have it both ways.

Let me try yet another version of the California argument, this time from one of my favorite foils, Jack Marshall:

The Electoral College was designed to prevent big states in a federal system from dictating to the other states, which might not share their culture or sensitivities. Imagine a big, wacko state like California dominating our politics. In fact, that’s exactly what would happen without the Electoral College. In the election just completed, Clinton won the Golden Bankrupt Illegal Immigrant-Enabling State by almost 4 million votes, while Trump got more votes than Clinton in the other 49 states and the District of Columbia. That’s why we have the Electoral College, and a more brilliant device the Founders never devised.

Reducing the power of large states may very well have been the intent of the designers of the Electoral College, but it’s a morally dubious goal. The Constitution was negotiated by representatives from the states, and under the Articles of Confederation, each state counted equally. Delegates from the larger states felt this was unfair, since they represented the interests of more people. Because of this conflict, the U.S. Constitution is a compromise between proportional representation and representation by state. This shows up in the different methods of choosing members of the House and Senate, and in the related method for allocating electoral voters.

However, as a matter of equity and fairness, I don’t see how you can claim that all people are equal when using non-proportional representation. Anything other than exactly one person, one vote gives some citizens unfair advantages over others. Wyoming has three electors, roughly one for every 200,000 residents, whereas California has 55 electors, which works out to about one for every 700,000 residents. All other things being equal, if California voters get one vote for president, then Wyoming voters are each getting about 3.5 votes. You can argue that this system was a necessary compromise at the time, but there’s no way it’s a fair arrangement today.

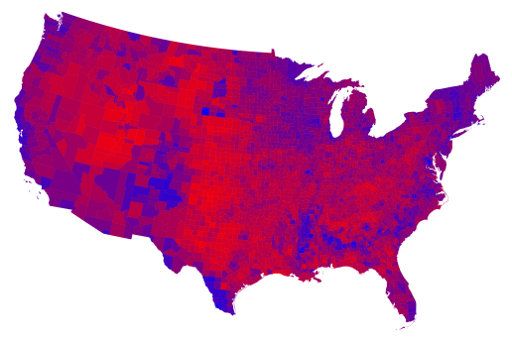

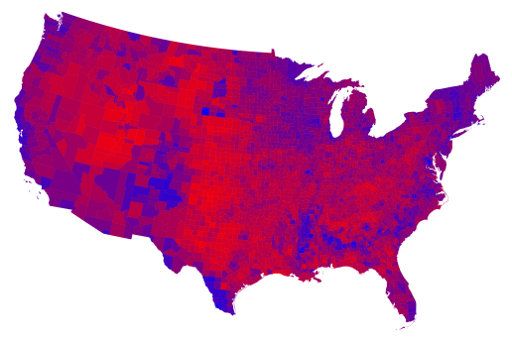

Furthermore, the idea that California would dominate our politics under a popular vote system is nonsense because under a popular vote system, there are no states. Imagine you had a giant map of the entire United States showing every voter colored red or blue to indicate which presidential candidate they voted for. It would be a vast mix of shades of purple, with deep blue cities and vast open patches of red, all made up of 125 million tiny colored specks, one for each voter. It would look a bit like this:

(That actually shows county results from 2012, tinted proportionately, but I think it’s close enough to demonstrate the idea.)

Now imagine drawing a box on that map large enough to contain 13 million voters, a little more than 10% of the electorate. If you arbitrarily draw the box so that it contains a lot of red, you might be able to get a 2:1 ratio of Republicans to Democrats, so that Republicans outnumber Democrats by 4 million votes. On the other hand, if you happened to draw a box that contains a lot of blue, you might get the opposite result: 4 million more Democrats in the box than Republicans. It’s the same map, and the same popular vote totals either way.

When folks like Gehl and Marshall argue that Hillary only won the popular vote because of California, all they’re doing is drawing a box, this time following the California border. The fact that they can draw such a box doesn’t prove that the people in the box “dominate” the election. It’s just an arbitrary box.

You might object that this isn’t an arbitrary box, because it’s the State of California. Yes it is, and under our current electoral voting system, the voters within its boundaries control a block of 55 electoral votes, about 20% of the 270 votes needed to win, and they all go to whoever wins the popular vote within the state, even if they only win by a little. That makes California pretty important to control.

But if we switch to a nationwide popular election, no one has control of California, because state boundaries don’t matter any more. The voting totals reported on election night might be organized by state for administrative purposes, with fancy computerized maps and everything, but all that really matters in a popular election is the total vote. The State of California becomes just an arbitrary collection of 13 million individual voters based on where they happen to live. It’s no more significant than grouping them by the first letter of their last name, and it’s no more sensible to talk about California domination of the popular vote than to argue about whether people whose names start with “S” are dominating the election.

California is a vast and diverse state, with cities, small towns, and farmland. It’s a home for a gigantic tech sector, it’s a center for international trade, and it’s a major exporter of agricultural products and entertainment. It has given us Jerry Brown and Ronald Reagan, and it’s a mistake to think of its residents as a uniform collection of bankrupt illegal immigrant-enabling leftists, as some would have it.

Basically, saying Hillary only won because of California is a silly game. You could just as easily say that Trump only won because of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, which have a combined population of about ten million fewer people than California. Heck, if you just nudged the borders of those three states enough to push about 100,000 Republican voters into neighboring states, Hillary would have won the electoral vote.

To put it yet another way, the population of California is greater than that of Alaska, Arkansas, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, Rhode Island, Utah, and West Virginia combined. In a system where everybody counts equally, Californians are a large fraction of everybody — about 1/8 of the U.S. population — so why shouldn’t they have a proportionately large effect on the election?

I’m not saying there aren’t any good reasons for the Electoral College, but the California effect isn’t one of them. People who complain about the effect California would have in a popular election are just complaining that large numbers of people disagree with them, and in arguing for the Electoral College on that basis, they are arguing for partial disenfranchisement of those people.

Leave a Reply